Considerações sobre Tempo e Limite na produção e recepção da Arquitectura (1)

“ eppure io credo che, se ci fosse un po’ pìu de silenzio, se tutti facessimo un po’ de silenzio... forse qualcosa potremo capire! “

Federico Fellini

A especificidade do conhecimento disciplinar da Arquitectura expressa-se não só no que parece ser mais evidente, nomeadamente nas várias matérias que o conformam, mas de um modo igualmente importante, nos processos de formulação e desenvolvimento que lhe estão associados. Na abertura do seu ensaio “L’illusion de la fin ou la grève des événements” , Baudrillard(2) questiona-se sobre a possibilidade de um ponto de desvanecimento da História, servindo-se de uma citação de Elias Canetti(3): “ Uma ocorrência dolorosa: a de que a partir de um ponto preciso no tempo, a história deixou de ser real. Sem se aperceber disso, a totalidade do género humano de repente teria saído da realidade. Tudo o que sucedesse a partir daí já não seria em absoluto verdade, mas não nos poderíamos aperceber disso. A nossa tarefa e o nosso dever consistiriam agora em descobrir esse ponto e, até que déssemos com ele, não nos restaria outro remédio senão perseverar na destruição actual.”

Neste sentido, interessa-nos aqui reflectir sobre alguns aspectos do processo de produção da arquitectura contemporânea, nomeadamente sobre o fenómeno de compressão dos tempos actualmente associados à sua concepção, realização e recepção (consumo), questionando-nos sobre a possibilidade de nos encontramos nesse ponto de desvanecimento, e estarmos a viver uma mudança de paradigma na produção da Arquitectura, da qual decorrerá uma alteração igualmente paradigmática da especificidade e do entendimento do lugar da Disciplina e dos seus fautores. Parafraseando Canetti e face aos preocupantes sinais de desagregação disciplinar com que o presente cada vez mais nos brinda, creio que, se não reclamarmos de um pouco mais de tempo (... e de silêncio!) para reflectir sobre o sentido da nossa prática, outra coisa não faremos que não seja contribuir pare esse mesmo processo de desagregação.

Para um enquadramento histórico da evolução dos modos de produção da Arquitectura, servir-me-ei aqui mais uma vez da classificação proposta em 1973 por Broadbent(4), que identificava quatro modos de produção da Arquitectura, os quais embora se possa considerar que perduram até ao presente, correspondem de um modo sedimentar a uma determinada evolução histórica desta produção. Simplificadamente, eram eles os modos Pragmático, Icónico, Analógico e Canónico. De acordo com o primeiro modo de produção arquitectónica, que aquele autor classificou como Pragmático, o projectista utilizaria os materiais de construção que tem à mão, utilizando-os elementarmente de modo a adequá-los à resolução das necessidades básicas com que se confronta. O segundo modo, o Icónico, embora com o mesmo carácter empírico, corresponderia a uma produção de objectos referidos a modelos, que se constituíram em nome de um saber instituído por uma longa prática anterior de construções bem sucedidas. Já o modo Analógico era definido por Broadbent com um carácter que representa uma evolução em relação aos modos anteriormente descritos. Seria um processo em que novas formas visuais, ao invés de se gerarem à custa da reprodução fiel de modelos existentes, são criadas através de diversos tipos de analogias. Para além do sentido mais evidente e metafórico normalmente atribuído a este processo analógico, interessa aqui referir o modo como os desenhos em si mesmos são utilizados e entendidos como análogos de realidades prospectivas referidas ao universo da arquitectura e da construção. O fascínio que o desenho propriamente dito exerce sobre os projectistas, ao desenvolver uma ideia de padrão e regularidade, permitindo questionar uma relação com uma ordem superior e transcendente, expressou-se muitas vezes sob a forma de traçados regrantes. É esta forma de projectar, apoiada em parâmetros ou cânones de diversa natureza, tendo em vista a obtenção de ideais de proporção e harmonia, que é descrita como modo Canónico. Como sabemos, é sobretudo a partir da Renascença, desde a descoberta em 1414 de uma cópia manuscrita de De architectura de Vitrúvio, que se assiste ao desenvolvimento de um grande número de tratados de arquitectura que definem regras e modelos canónicos para a composição e projectação dos edifícios. Este modo deve no entanto ser entendido para além da sua origem clássica, pois num sentido lato a sua utilização perdurou até hoje em dia na prática dos arquitectos, desde os ensaios com o Modulor propostos por Corbusier no séc. XX, até à utilização, por exemplo, de qualquer simples grelha ou artefacto gráfico intencionalmente utilizado pelo projectista para orientar ou estruturar decisões de projecto. É evidente que a referenciação destes modos, como qualquer processo de classificação, corresponde a uma enorme simplificação daquilo que sabemos ser o complexo processo de concepção da Arquitectura. Mas face a este quadro, e apesar da diversificação atrás exposta, será para nós suficiente desde já poder afirmar que a primeira grande alteração de paradigma na produção da arquitectura se dá com a introdução, do Desenho como suporte operativo da concepção. Na verdade, é sobretudo através da sua utilização e nomeadamente do esquiço como meio de antecipar o resultado pretendido, que o conceito de Projectar se transforma naquilo que perdurou até aos nossos dias, e que a própria figura do arquitecto como trabalhador de “mãos limpas”, de intelectual, ganhou os contornos que, sem alteração de maior, chegaram praticamente até ao final do séc. XX. No entanto, em qualquer um destes paradigmas impõe-se um tempo a que chamarei o “tempo da mão”. Este tempo, associado a uma certa artesania, contribuiu para uma permanência que se processa tanto no processo da concepção/projecto como no da realização/construção. Associado a este tempo e por razões que ultrapassam já as dos meios de produção, reconhecemos nos objectos arquitectónicos uma permanência também nas suas dimensões materiais, simbólicas e significantes, que os fenómenos de aceleração introduzidos pelos mecanismos da sociedade de consumo vieram destruir. Para a estruturação do argumento que pretendo desenvolver, resumiria a diferenciação que estará na base dessa nova mudança de paradigma que procuro evidenciar, através de uma análise baseada nas seguintes vertentes: Concepção, Realização (construção), Recepção (interpretação/uso). Segundo o paradigma anterior (clássico?) da produção da Arquitectura, teríamos então um tempo de Concepção baseado num conhecimento tácito e empírico associado à sua transmissão numa relação mestre/discípulo (da formação ao exercício da profissão) e num “tempo da mão” associado aos próprios meios operatórios e operativos de suporte da concepção. O fenómeno de uma certa centralização do trabalho no mestre/auto, não deixa de participar no condicionamento da clássica “lentidão” do processo de concepção.

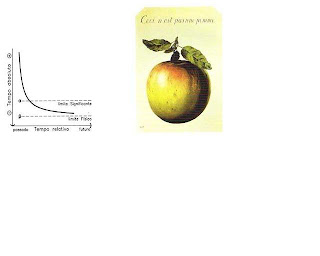

Mas, também na vertente da Construção, este é um momento claramente marcado pelo carácter artesanal dos processos do acto de construir, no qual a inclusão de um saber de artífice na execução da obra e dos detalhes, obrigava a um tempo de construção que no início não poucas vezes excedia até a vida de muitos dos seus agentes. De algum modo, a dificuldade na execução, tanto na concepção como na construção, introduzia incontornavelmente o tempo como factor potenciador da inscrição dos elementos em presença. Acresce o facto de que este é um momento histórico no qual o enquadramento das transformações sociais e culturais se constituía ele mesmo num referencial de relativa estabilidade e permanência, conferindo uma dimensão sincrónica ao tempo associado a estas vertentes da produção, construção e obsolescência (material, funcional e significante) do objecto arquitectónico. Analisemos agora as alterações produzidas por esse impressivo fenómeno de aceleração e compressão do tempo que se abate gradualmente, sobretudo a partir da Revolução Industrial, sobre o processo de produção e recepção da Arquitectura. Introduz-se assim aquilo a que, por oposição e para simplificação do discurso, chamarei agora o “tempo da máquina”, que nos nossos dias é indissociável não só da mais recente Revolução Tecnológica, como também de uma lógica avassaladora imposta pela nova “Sociedade de Hiperconsumo” de que nos fala, por exemplo, Gilles Lipovetsky no seu mais recente ensaio(5). No que se refere à primeira vertente – Concepção – essas alterações devem-se desde logo ao advento de novos meios de produção, expressos inicialmente na banalização da utilização do papel e posteriormente na simplificação dos meios de reprodução. Depois, devem-se também aos princípios da divisão social do trabalho na própria área da concepção, de que, na sua dimensão mais expressiva, é exemplo pioneiro a prática corporativa dos gabinetes norte-americanos do princípio do século XX(6). Finalmente, a introdução sucessiva de princípios de industrialização na construção, faz com que o próprio projecto se envolva progressivamente com uma sistematização e indiferenciação de muitos dos detalhes utilizados, o que permite uma enorme racionalização dos tempos de concepção e produção dos projectos. A adopção em massa dos meios informáticos que hoje tão bem conhecemos, com todas as consequências daí decorrentes, para o melhor e para o pior e que agora me coíbo de desenvolver, é tão somente o último elo deste processo de aceleração que tenho vindo a enfatizar. Mas também na segunda vertente que referimos – Construção – a aceleração produzida pela inexorável lógica de industrialização capitalista, e progressivo afastamento dos artífices do processo de construção, produziu uma crescente indiferenciação nos detalhes, de que se ressentiu inevitavelmente a qualidade global da construção que em consequência dessa precarização, salvo situações de excepção, conduziu a uma aceleração da chegada do momento de obsolescência. No que se refere à terceira vertente em estudo – Recepção (interpretação/validação e uso) – os fenómenos de extraordinária e progressiva aceleração no consumo atrás citados provocam finalmente, uma absoluta dessincronia entre os vários níveis de obsolescência, (material, funcional e significante) que venho referindo. Assim, contrariamente ao paradigma anterior, no qual a dimensão material e até a validação simbólica de um objecto arquitectónico era frequente sobreviver em muito a sua dimensão funcional, deparamo-nos, cada vez mais, com edifícios cuja função permanece válida face a um contentor ou a uma imagem tornados obsoletos por via desta vertigem de consumo e indiferenciação e precarização da construção. Sem querer assumir um discurso apocalíptico sobre o fim da Arquitectura, já por outros tantas vezes em vão anunciado, e apesar da impossibilidade de recuo histórico, não deixa de ser para nós arquitectos fundamental reflectir sobre o momento que vivemos, no que se refere às actuais condições de produção e recepção da Arquitectura. Assim sendo, aquilo que me proponho fazer, é especular sobre a possibilidade de que, no caso da produção e recepção da Arquitectura, este “vanishing point” de que nos falava Baudrillard se processe antes num intervalo formado pelo que eu passo a designar por “dissociação de limites”. Numa metáfora simples, todos nós ao provarmos, por exemplo, algum fruto actualmente produzido segundo técnicas que aceleram extraordinariamente o tempo do seu crescimento, constatámos que, por detrás de uma mesma aparência, não reside já a memória completa em todas as suas vertentes concretas e perceptivas que preservamos ainda do seu referente “natural”. Ou seja, antes de,por via da técnica, termos atingido o limite físico do possível, ultrapassámos já algures um outro limite, onde a realidade global e perceptiva desse fruto correspondia ainda à memória que dele tínhamos.

Se retomarmos de novo o território da Arquitectura, a primeira das linhas definidoras deste intervalo ( ver diagrama em anexo ), será portanto a de um hipotético limite concreto, físico, para a possibilidade de compressão no tempo da sua produção e recepção ( linha ? ). Na realidade, tal como na metáfora do fruto “natural” e do seu alter ego tecnicamente acelerado, é inevitável considerar que, embora esse limite tenda para o infinito, em algum momento a curva hiperbólica de compressão que o representa atinja um ponto que não será fisicamente possível ultrapassar. No entanto, a questão que pretendo aqui suscitar também para a Arquitectura, é a de que chegados a este limite, teremos já ultrapassado um outro ( linha ?), a partir do qual o objecto arquitectónico já não poderá ser definido como tal, à luz dos conceitos que a cultura e a crítica da arquitectura os têm dominantemente tratado, no âmbito do paradigma clássico que procurei circunscrever. Nesta perspectiva, o que pretendo portanto afirmar, é que, ultrapassado o limite sincrónico onde o tempo condicionado pela técnica ainda se articulava “naturalmente” com o tempo do pensamento disciplinar, será no intervalo desta \"dissociação de limites que situa grande parte da produção da arquitectura contemporânea. E a propósito da produção situada neste intervalo, na sequência da metáfora que utilizei anteriormente, apetece parafrasear Magritte dizendo “ceci n’est plus une pomme” ...

Desde logo se coloca portanto a própria questão da designação e redefinição destes novos produtos(7). De entre os vários autores que de algum modo se têm confrontado com esta questão(8), citaria aqui a contribuição de Peter Eisenman, quando distingue Arquitectura de Infraestrutura(9). Eisenman sugere que é a perda da dimensão crítica contemporaneamente associada aos objectos de arquitectura por via do seu processo de mediatização que os transformam em meras infraestruturas (para este facto não é indiferente a perda do lugar específico e o território global para que remetem, bem como, diria eu, os seus próprios autores, que se envolvem cada vez mais activamente na sua promoção). Para Eisenman, através da História, a Arquitectura sempre conteve uma dimensão crítica por via da transgressão das ideologias existentes. Embora em certa medida a Arquitectura seja considerada como estando animada pelo espírito do tempo, segundo ele, a sua dimensão crítica sempre se construiu na resistência a esse Zeitgeist. Foi essa a dimensão transgressora de objectos como a biblioteca Laurenziana de Miguel Ângelo ou o convento de La Tourette de Le Corbusier, face aos respectivos tipos então existentes. Ora, ainda segundo Eisenman, os media, estando aliados à sociedade de consumo, estão também contra a ideia de transgressão, contra a ideia de qualquer mecanismo ideológico associado à Arquitectura. Na verdade, a ideologia não é interessante para os media, pois eles consomem e regurgitam qualquer coisa que tente resistir. Qualquer mensagem com conteúdo ideológico [crítico] será exactamente contra o funcionamento dos media(10). No entanto, permito-me acrescentar ainda à sugestão de Eisenman a ideia de que a dimensão simbólica, através de todas as formas de expressão plástica, formal e imagética que possam contribuir para os processos de sedução inerentes ao consumo, participa obviamente do quadro de funções acomodadas por estas novas infraestruturas, na própria lógica iconográfica de uma sociedade de (hiper)consumo, ela própria agente deste fenómeno de aceleração e compressão do tempo que temos vindo a referir. Eisenman consuma a distinção anterior através de uma definição das noções de Perícias (skills) e de Disciplina. Para ele, as Perícias correspondem aos instrumentos e às técnicas necessárias para fazer a Arquitectura; já a Disciplina refere-se às ideias que constroem o discurso. Sem as Perícias, não nos podemos expressar; sem a Disciplina não podemos ter uma dimensão crítica. Quanto maior for a Perícia, mais difícil será ter Disciplina. Sem Disciplina é impossível fazer Arquitectura transgressora. Para Eisenman então, a Perícia permite construir o conhecido, a Disciplina permite construir o possível(11) . Esta questão das perícias que aqui trago, entendida na sua dimensão técnica, é indissociável das capacidades dos meios de produção colocados hoje em dia à disposição da Arquitectura nas três vertentes que temos vindo a considerar, (Concepção/Construção/Recepção), pelo que é à luz desse entendimento do papel que as novas tecnologias desempenham neste fenómeno de aceleração do tempo de produção e recepção da Arquitectura que poderíamos atender, uma vez mais, à reflexão forçosamente mais generalista de Baudrillard. Diz ele: “A aceleração da modernidade, técnica, de acontecimentos, acessória, mediática, a aceleração de todos os intercâmbios, económicos, políticos, sexuais, conduziu-nos a uma velocidade de libertação tal, que saímos da esfera referencial do real e da história. Estamos “libertos” em todos os sentidos do termo, tão libertos que saímos de um espaço tempo determinado, de um horizonte determinado no qual o real é possível porque a gravitação ainda é suficientemente forte para que as coisas se possam reflectir, e portanto ter alguma duração e alguma consequência.(12) (sublinhado nosso)

Em claro contraponto àquele processo, e também a propósito da produção da Arquitectura, Vittorio Lampugnani, no seu “Elogio à Lentidão”(13) fala-nos de um processo lento e sedimentar, do qual como nos recorda, resultava uma qualidade no projecto por vezes já difícil de encontrar: a de densidade. Densidade de conceitos, de ideias e de implicações. Na verdade, cada vez mais, apoiada pelo desenvolvimento das Perícias, a pressão para a redução dos prazos de concepção (e construção) é tal - a ponto de cada vez mais arquitectos a banalizarem, considerando-a “natural” - que tem sido inevitável constatar a diminuição do lugar da Disciplina, daí resultando a gradual perda de densidade a que se referia Lampugnani(14). Devemos então permanentemente reclamar desse tempo não só da mão, como também do pensamento que constrói a Disciplina, pois, de novo como dizia Baudrillard, “certa lentidão (quer dizer, certa velocidade, mas não demasiada), certa distância, mas não demasiada, certa libertação (energia de ruptura e de mudança), mas não demasiada, são necessárias para que se produza esta espécie de condensação, de cristalização significativa dos acontecimentos a que chamamos história, esta espécie de explicação coerente das causas e dos efeitos a que chamamos o real.”(15) Para uma cultura economicamente periférica como a nossa – e face aos contornos actuais do fenómeno da arquitectura contemporânea, massivamente divulgada nas revistas da especialidade e com tanto eco nas escolas de Arquitectura –, a ser certo que nos encontramos neste intervalo paradigmático provocado por aquela “dissociação de limites” que procurei estabelecer, talvez este apelo à lentidão, à crítica disciplinar e à memória, seja não a mera expressão de um conservadorismo nostálgico, mas sim uma oportunidade e um modo de resistir a novas formas globais de colonialismo cultural e não só. Mas isso serão contas de um outro rosário...

Jorge Spencer, arquitecto Professor auxiliar na Faculdade de Arquitectura | UTL

Referências no texto:

(1) Este texto foi escrito em Agosto de 2007 a partir de uma palestra proferida em Julho de 2005 na Livraria Eterno Retorno, no Bairro Alto em Lisboa.

(2)Jean Baudrillard, L’illusion de la fin ou la grève des événements (versão castelhana: La ilusión del fin. La huelga de los acontecimientos. pág.9).

(3)Elias Canetti (Bulgária, 25 Julho1905 –Zurique, 14 de Agosto1994), Nobel de Literatura em 1981.

(4)Cf. Geoffrey Broadbent, Design in Architecture : Architecture and the Human Sciences.

(5)Cf. Gilles Lipovetsky, Le Bonheur Paradoxal (versão portuguesa: A Felicidade Paradoxal: ensaio sobre a sociedade do Hiperconsumo)

(6)Veja-se a este respeito a dissertação de doutoramento de Pedro Ravara: \"A consolidação de uma prática: do edifício fabril em betão armado nos EUA ao modelo europeu\", no capítulo 5 referente à prática do arquitecto Albert Kahn. (Lisboa – FAUTL, 2007).

(7)Recordemo-nos como no campo das Artes, durante o séc. XX surgiram novas designações como “instalação” ou “performance” para designar formas de expressão artística que já não cabiam nas designações tradicionais de Pintura, Escultura, etc., arrastando nesse processo uma própria redefinição dos limites e contextos da produção da Arte em geral.

(8)Vejam-se a este respeito os contributos dados pelas obras da socióloga Saskia Sassen.

(9)Cf. Peter Eisenman, Eleven points on Knowledge and Wisdom.

(10)Idem, ibidem.

(11)Idem, ibidem.

(12)Jean Baudrillard, Op.cit. pág.9.

(13)Vittorio M. Lampugnani, Elogio della Lentezza.

(14)A este respeito e no quadro das excepções, posso citar o exemplo do português Siza Vieira, que tem utilizado justamente o poder que em parte lhe é conferido pela mediatização da sua obra, para reclamar o tempo necessário ao exercício da “Disciplina”.

(15)Jean Baudrillard, Op. cit. pág.10.

Bibliografia

Baudrillard, Jean, L’illusion de la fin ou la grève des événements, Paris - Éditions Galillée, 1992 (versão castellana: La ilusión del fin. La huelga de los acontecimientos. Madrid – Anagrama 1997)

Broadbent, Geoffrey, Design in Architecture: Architecture and the Human Sciences, Londres – John Wiley and Sons, 1973.

Eisenman, Peter, “Eleven points on Knowledge and Wisdom”, Anywise, MIT Press, 1996.

Lampugnani, Vittorio. M., \"Elogio della Lentezza\"Domus nº744 - Dezembro de 1992

Lipovetsky, Gilles, Le Bonheur Paradoxal, Paris- Editions Gallimard,2006 (versão portuguesa: A Felicidade Paradoxal: ensaio sobre a sociedade do Hiperconsumo, Lisboa - Edições 70, 2007.)

Spencer, Jorge, Aspectos Heurísticos dos Desenhos de Estudo no Processo de Concepção em Arquitectura, Dissertação para Doutoramento em Arquitectura pela FAUTL, 2000.